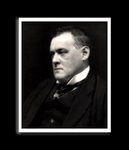

Orestes Brownson was a late convert to Catholicism in the 19th century, and described by the Ven. John Henry Cardinal Newman as "The Greatest thinker the United States has ever produced."

Orestes Brownson was a late convert to Catholicism in the 19th century, and described by the Ven. John Henry Cardinal Newman as "The Greatest thinker the United States has ever produced." From The Boston Quarterly Review; 3 (1840): 368-370

In regard to labor, two systems obtain: one that of slave labor, the other that of free labor. Of the two, the first is, in our judgment, except so far as the feelings are concerned, decidedly the least oppressive. If the slave has never been a free man, we think, as a general rule, his sufferings are less than those of the free laborer at wages. As to actual freedom, one has just about as much as the other. The laborer at wages has all the disadvantages of freedom and none of its blessings, while the slave, if denied the blessings, is freed from the disadvantages.

We are no advocates of slavery. We are as heartily opposed to it as any modern abolitionist can be. But we say frankly that, if there must always be a laboring population distinct from proprietors and employers, we regard the slave system as decidedly preferable to the system at wages.

It is no pleasant thing to go days without food; to lie idle for weeks, seeking work and finding none; to rise in the morning with a wife and children you love, and know not where to procure them a breakfast; and to see constantly before you no brighter prospect than the almshouse.

Yet these are no infrequent incidents in the lives of our laboring population. Even in seasons of general prosperity, when there was only the ordinary cry of "hard times," we have seen hundreds of people in a not very populous village, in a wealthy portion of our common country, suffering for the want of the necessaries of life, willing to work and yet finding no work to do. Many and many is the application of a poor man for work, merely for his food, we have seen rejected. These things are little thought of, for the applicants are poor; they fill no conspicuous place in society, and they have no biographers. But their wrongs are chronicled in heaven.

It is said there is no want in this country. There may be less in some other countries. But death by actual starvation in this country is, we apprehend, no uncommon occurrence. The sufferings of a quiet, unassuming but useful class of females in our cities, in general seamstresses, too proud to beg or to apply to the almshouse, are not easily told. They are industrious; they do all that they can find to do. But yet the little there is for them to do, and the miserable pittance they receive for it, is hardly sufficient to keep soul and body together.

And yet there is a man who employs them to make shirts, trousers, etc., and grows rich on their labors. He is one of our respectable citizens, perhaps is praised in the newspapers for his liberal donations to some charitable institution. He passes among us as a pattern of morality and is honored as a worthy Christian. And why should he not be, since our Christian community is made up of such as he, and since our clergy would not dare question his piety lest they should incur the reproach of infidelity and lose their standing and their salaries? . . .

The average life--working life, we mean--of the girls that come to Lowell, for instance, from Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont, we have been assured, is only about three years. What becomes of them then? Few of them ever marry; fewer still ever return to their native places with reputations unimpaired. "She has worked in a factory" is almost enough to damn to infamy the most worthy and virtuous girl. . . .

Where go the proceeds of their labors? The man who employs them, and for whom they are toiling as so many slaves, is one of our city nabobs, reveling in luxury; or he is a member of our legislature, enacting laws to put money in his own pocket; or he is a member of Congress, contending for a high tariff to tax the poor for the benefit of the rich; or in these times he is shedding crocodile tears over the deplorable condition of the poor laborer, while he docks his wages 25 percent. . . . And this man too would fain pass for a Christian and a republican. He shouts for liberty, stickles for equality, and is horrified at a Southern planter who keeps slaves.

One thing is certain: that, of the amount actually produced by the operative, he retains a less proportion than it costs the master to feed, clothe, and lodge his slave. Wages is a cunning device of the devil, for the benefit of tender consciences who would retain all the advantages of the slave system without the expense, trouble, and odium of being slaveholders.

3 comments:

Thank you for posting something regarding Orestes Brownson. I have only just discovered him. It is too bad that more modern protestants do not do what he did or become as learned as he was.

I know! much like Chesterton, he is a convert discovered only lately, although Chesterton is much more ubiquitous now. It is always fascinating to me, how people of great account are not remembered, or for a time are forgotten! In the 13th century, no one took much notice of St. Thomas or of St. Bonaventure in terms of accepting them as great thinkers in university life. The real master at their time was Alexander of Hales, and he eclipsed every thinker around him. Today, even an agnostic has heard of St. Thomas Aquinas, but Catholic students in philosophy might never hear the name of Alexander of Hales.

So with Brownson. It is as if the protestant culture at the time willed to forget him in a way Anglicanism could not forget Newman.

Here is a link for a free book at google books concerning Orestes Brownson:

http://books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC04620476&id=j0OqLx9h9UEC&pg=RA2-PA257#PPP3,M1

Philip I believe it is, it is up to us and people like us to put a mirror up to the face of the Church in America.

Post a Comment